Happening Now: Trump takes the lead in US presidential race

Half a century later, political symbolism of ‘rumble in the jungle’ lives on

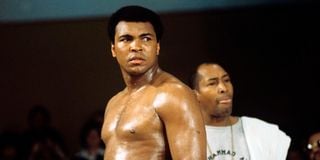

US heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali during a training session in Munich, Germany on May 15, 1975.

Fifty years ago today, Kinshasa and Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, became the centre of the world. For one night.

The Stade du 20 mai was the arena. The contenders? Muhammad Ali was facing George Foreman. Ali would become a ‘world champion’ after knocking out his opponent in a fight named ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, to refer to both the fact that these were the leading boxers of their time coming to an African arena for the first time, but also a cheek reference to the idea that Africa was still unexplored and a jungle.

The 'Rumble in the Jungle' became a worldwide event, broadcast in the US and several other countries. For the Congo, it became a marketing coup for Joseph Désiré Mobutu, then president of Zaire.

This is how it began. In the US, at a time when the great black boxing champions were making the headlines for their sporting success, a professional boxing promoter was brimming with bold initiatives. His name was Don King. In 1974, he arranged a fight between the then Olympic and world champion George Foreman and the former world champion Muhammad Ali. Both heavyweights.

Don King knew he was trying to make a winning bet. But he needed $10 million to pay the two challengers. He didn’t have it. Thousands of miles from New York, where Don King was based, Mobutu Sese Seko was prepared to offer that astronomical sum.

Mobutu had been president of Zaire for nine years and was accustomed to offering his fellow citizens with world-famous entertainment events. In 1967, he invited Brazilian football legend Pele and the entire Brazilian national team to Kinshasa; in 1969, he invited the American crew of Apollo 11 to Kinshasa after they had landed on the moon. For him, the fight between the two American champions was an excellent opportunity to gain worldwide publicity. At the time, Zaire's economy was flourishing, thanks to skyrocketing global copper prices.

Former President of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) Mobutu Sese Seko.

In 1974, Mobutu introduced his policy of 'recourse to authenticity', a policy that consisted of telling the people of his country and black people to rediscover their pride in being black. Mobutu wanted to affirm that black people were capable. The Zairean leader seized the opportunity to organise a "black struggle". Large posters in the streets of Kinshasa heralded the success of the leader's policy. "A fight between two black men, in a black nation, organised by black people and watched by the whole world, is a victory for Mobutuism," read the posters that dotted the Zairian capital at the time, according to photographs now displayed in Kinshasa museums.

The Zairean president had already created the MPR, the country's only political party. He had also renamed the Congo as Zaire. He also wanted to establish himself as a great African leader. So, through the various events, "it was also a question of competing with Léopold Cédar Senghor, the former Senegalese president, whose country had hosted the first World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966," wrote Eddy Ntambwe, a professor in Kinshasa.

When Ali and Foreman met in Kinshasa on the sidelines of their fight, a music festival had brought together the world's greatest black musicians in Kinshasa. "From Latin America came Celia Cruz and Johnny Pacheco, from the US B.B. King, the Pointer Sisters, Sister Sledge and James Brown. Saxophonist Manu Dibango and South African singer Miriam Makeba shared the stage with the great stars of Zairean music. Old Wendo Kolosoyi, the father of rumba, was there, along with Franco and his TP OK Jazz, Tabu Ley..." writes David Van Reybrouck in his book Congo, Une histoire.

In Kinshasa, the public had largely decided to support Mohamed Ali. In the Kinshasa neighbourhoods where he trained, young people and children chanted: "Ali, Boma ye" (Ali, kill him). The former world champion's popularity in Africa was undoubtedly due to his commitment to civil rights, which he had begun a few years earlier at the height of racial segregation in the United States. In the eyes of the Zairians, he was seen as one of their own, whereas George Foreman was simply seen as an American. Mohamed Ali, who had been Cassius Clay, had changed his name by embracing Islam. He arrived in Zaire, where Mobutu had banned Western names. Mobutu himself set an example by changing his name from Joseph Désiré Mobutu to Mobutu Sese Seko. What Muhammad Ali and Mobutu had in common was their pride in being true blacks. Both detested Western "arrogance". And so, as if by magic, Ali became popular in several African countries. In 1964, the boxing champion met Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana.

In Zaire in 1974, the stakes in this fight were threefold: for 32-year-old Mohamed Ali, it was to regain the heavyweight title of world champion, which he had been stripped of for three and a half years for refusing to fight in Vietnam. For 25-year-old George Foreman, it was about taking on Ali and winning the $5 million that Mobutu had staked through professional boxing promoter Don King.

For the former president of Zaire, it was a matter of propaganda and asserting himself as a great African leader.

Mobutu is long gone. But in Kinshasa these days, politicians like to talk about Congolese heritage. Last week, President Felix Tshisekedi told the public that the country must adapt to a political and legal system that is truly Congolese. He has proposed that a new constitution be written entirely by Congolese, to replace the current supreme laws, which he says were written by "foreigners [who] live abroad".